When Productivity Becomes Punishment: Rebooting My Life After Burnout

“What looked like strength was actually survival.”

For most of my adult life, I’ve been obsessed with progress. I measured my worth in commits, coursework, and creative output. I was always looking for the next thing to do, the next project to start, the next challenge to conquer. If I wasn’t building something, I was failing. I had to be busy. The idea of slowing down felt like weakness. Output was the measure of my worth.

After having kids and dealing with their medical issues and diagnoses, I realized something that was obvious in hindsight: I have had ADHD my entire life. I have always (with the exception of a few years post car accident, but that’s another blog post) performant. I have always loved achieving the highest marks I was capable of, and I have always been a perfectionist. When my capability to focus was truly dialed in after my ADHD diagnosis and subsequent treatment, I felt like I really turned a new corner. I felt like my potential was limitless. And I set out to fill my life with as much productivity as I could. I fell in love with applied AI and machine learning, particularly in regards to analytics, data science, and predictive modeling. I made the spontaneous decision to pursue a degree in AI/ML, after not being in school for 15 years. We had just had our fourth child, I was busy in my career, and I opted to add more to my plate. In hindsight, I was in a state of chronic overproductivity. It was my coping mechanism, and it was working.

It took me a long time to realize that what looked like discipline was often something else: avoidance. According to Productivity as a Trauma Response by PsychCentral, people who’ve lived through chronic stress or emotional upheaval sometimes stay constantly busy to outrun their own feelings. Work becomes a shield; one that protects us from guilt, fear, and self-disappointment. It was my method of ignoring the areas of my life that could be classified as shortcomings. I refused to acknowledge that I had failures and weaknesses, and investigate the root cause of these failures and how to best improve.

This relatively recentintrospection hit me hard. Because I recognized myself immediately. My endless productivity wasn’t ambition; it was anesthesia. The busier I was, the less I had to feel.

The Peak Before the Fall

Between 2021 and mid-2024, I was operating at what I thought was peak performance. I was working full time and receiving praise and recognition for my work, studying full time and earning honors and awards, and parenting four kids. Every hour of the day was accounted for. I told myself I was thriving. I was exceeding expectations in all areas of my life, and I was proud of my accomplishments.

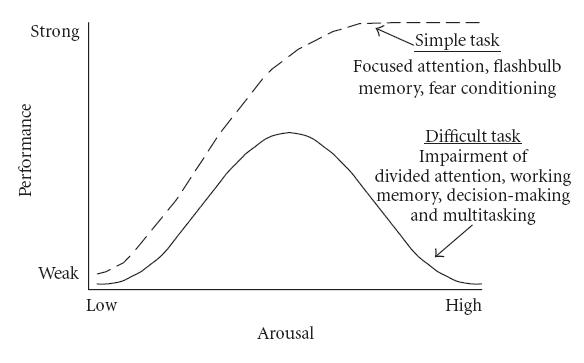

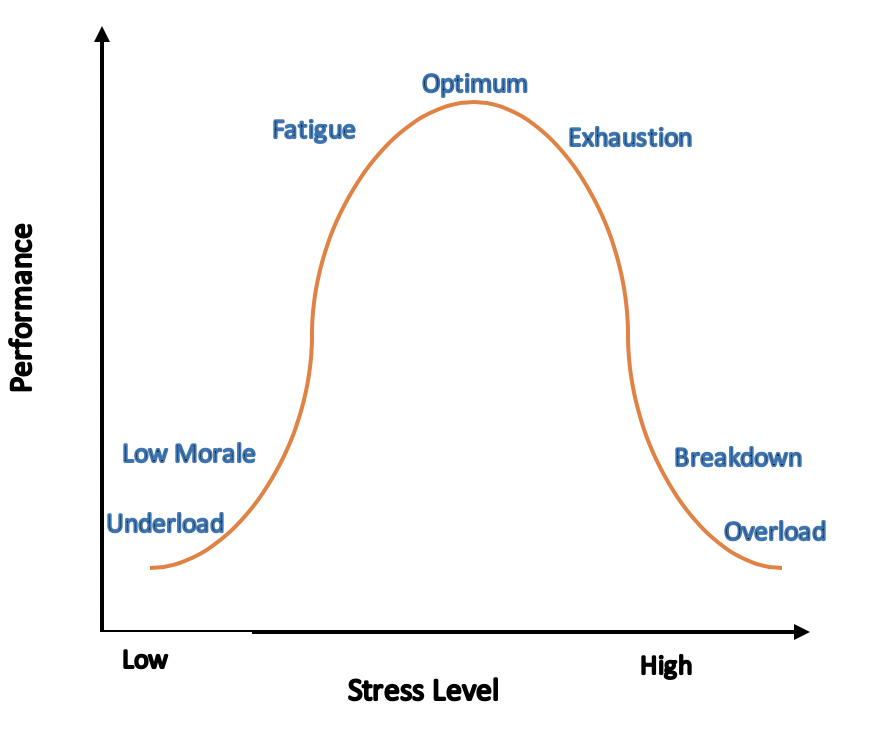

If you’ve ever seen the Yerkes–Dodson stress-performance curve, you know the shape: a gentle rise as moderate stress sharpens focus, followed by a steep drop when the load becomes unsustainable. For a while, I balanced on that curve’s sweet spot. I was constantly sitting at something like 95% of maximum load regarding stress and responsibility. Then I fell off the edge.

The Breaking Point

Then came two events that rewired my world. My daughter went through a traumatic experience that shattered her sense of safety and left my wife and I questioning our ability to protect her, our capability to parent. Not long after, my wife faced one of her own. Just one of these events would have been enough to collapse my house of cards, but together they left me utterly shattered and unable to function enough to pick up the pieces.

The following months the hardest of my life, even more so than the years following my car accident. I was already maxed out, emotionally and physically. Suddenly, I was trying to carry grief, fear, and more responsibility than I could possibly handle. I had always been the strong one, the one who could handle anything, the one who could keep going no matter what. But now I was the one who was broken. I was the one who couldn’t keep going. I was the one who was lost. But five people depended on me, so I desperately tried to simply ignore it. It didn’t work. I collapsed. I was in a state of complete and utter burnout. I could not function. I could not think. I was afraid to sleep because it all manifested in nightmares. All I could do was feel, with no escape.

Since that time, I have learned about allostatic load, a term coined by neuroscientist Bruce McEwen (1998). It describes the wear and tear our bodies accumulate from chronic stress—the physiological cost of constantly being in survival mode. Even after the crisis passes, your body doesn’t forget. It stays on high alert. Fight, flight, or freeze persists in the background, even when you are not consciously aware of it.

Although I could not define it or describe why, I knew I was not the same person I was before the events, that something was fundamentally broken. Even small tasks felt impossible. I’d stare at code or schoolwork for hours and get nowhere. My energy evaporated. My capacity to parent disappeared. My system had gone offline.

The Science of Burnout

Per the World Health Orgnization, burnout is defined as an “occupational phenomenon” rather than a medical condition:

Burn-out is a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions:

- Feeling of energy depletion or exhaustion

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job

- Reduced professional efficacy

In 2025, Monteiro Ribeiro et al. published research linking instability in software engineering environments directly to burnout. That finding made something click for me. I wasn’t uniquely broken; I was another engineer who’d hit the limits of human capacity in a profession that quietly rewards self-erasure. Add in the quiet, still-present societal pressure on the role of the father and husband, and the pressure to be the best at everything, and you have a recipe for burnout.

In a December 2024 article, CIO.com published an article titled “Burnout: A chronic epidemic in the IT industry” which references an Upwork Research Institute survey that found that 71% of IT professionals report they are currently experiencing burnout. It is highest in software engineering and cybersecurity. A simple Google search will find many more articles on the topic. The CIO article is accurate in its assessment, this is a chronic epidemic. It is also systemic, and technical leadership needs to fully understand the root causes and embrace the responsibility to address them.

Personally, my overwhelmed state was not just emotional. The Cognitive Resource Depletion model (Franklin, Lerman & Hodas, 2017) explains that our mental battery for focus and decision-making is finite. Chronic stress drains it faster than it can recharge. That’s exactly what it felt like. The more I tried to push through, the worse I performed. The worse I performed, the guiltier I felt. So I pushed harder—and collapsed further. It became a closed feedback loop of exhaustion. This is a very real and very common experience for many people, and it is a major contributor to burnout. The key is to recognize the signs and symptoms early and seek help before it is too late.

The Crash

By mid-2024, I’d completely fallen apart. My motivation vanished. Deadlines passed untouched. Even simple family routines felt impossible to manage. There was no dramatic burnout moment, no single meltdown. It was quieter than that—just the steady erosion of who I thought I was. All the while, I was still trying to be the lighthouse for my wife and daughter, who were still dealing with their own dark days and traumas. I was drowning with no motivation to tread water, no energy to swim. Help was nowhere to be found.

It only escalated from there. I could not work, so income dried up. I could not parent and my kids needed me the most, particularly my daughter. My wife needed me to be her rock, and I wanted nothing more than to be what she needed me to be. But I was no rock, I had eroded. This family had lost its foundation. A misunderstanding escalated issues even further, and suddenly our eldest son, our 9 year old on the autism spectrum, suddenly had to deal with his own traumatic experience. He was terrified, and I was terrified for him. I was terrified for my wife, and I was terrified for myself. It seemed like every single time I thought I had hit rock bottom, I was wrong. I was wrong again. And again. And again.

The Reset

Through the months, things improved here and there. My wife completed her degree. The kids were getting through the school year. But I was still lost. I was still broken. I did not have the energy for my responsibilities, and I did not have the capacity to focus on anything. I was still in a state of complete and utter burnout and had nowhere to turn.

Finally, I was able to perform some part-time consulting work, but not anything more than half-time. I was still not able to parent at a level I was proud of, and I was still not able to focus on anything. I was still in a state of complete and utter burnout and had nowhere to turn.

After many months of this and discussing my despair and hopelessness with my wife, she suggested a full reset. I needed to get away from the environment that had been a source of a vast amount of my stress and frustration, and getting my wife elsewhere was going to help as well. After extensive research, we decided to invest in an immigration attorney service and started the process of getting a digital nomad visa for Spain. We had always talked about moving abroad, but now we were actually doing it. It was not an escape plan, it was an intentional reboot. The slower pace, the emphasis on family and time over output—it felt like the nervous system I’d been missing.

In the months since, I’ve been trying to unlearn old habits and patterns and rebuild myself. Trying to redefine productivity as something that serves me, not something that consumes me. The process has been anything but linear. Some days, I still slip back into the old loops—staying up too late working, filling my time to avoid emotion. Some days I am completely overwhelmed and feel the burnout that has still not fully subsided.

I am trying to teach myself how to have fun again, to find enjoyment. In my desperation to escape the reality of my stress and anxiety, I lost so much of what made me, me. I am not who I was, nor will I ever be again. It is hard to accept that, hard to acknowledge parts of me have shattered. Just writing it out is an emotional experience, but I suppose that’s part of the healing process. I try to focus on the opportunity to choose how I rebuild myself, how I rebuild my life, how I rebuild my family, how I rebuild my relationships, how I rebuild my career, how I rebuild my sense of self.

Redefining Productivity

These days, I’m trying to measure success differently.

- By how grounded I feel when I wake up, not how much I checked off a list.

- By the quality of time with my family, not the quantity of code shipped or grades earned.

- By trying to acknowledge and express my emotions, rather than avoiding them.

This blog reboot is part of that process. It’s a record of my rebuilding process, learning how to find a sustainable work/life balance, working on mindfulness, and prioritizing my mental health.

It is not consistent, constant growth, there is often no progress. In fact, there is often regression. But I am trying to focus on the opportunity to choose how I rebuild myself, how I rebuild my life, how I rebuild my family, how I rebuild my relationships, how I rebuild my career, how I rebuild my sense of self.

References

- PsychCentral. (2022). Productivity as a Trauma Response: Discover the “Busy Bee” Pattern.

- Monteiro Ribeiro et al. (2025). Software Engineering Instability and Burnout: Cognitive and Emotional Predictors.

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators: Allostasis and Allostatic Load. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171-179.

- Franklin, Lerman & Hodas. (2017). Cognitive Resource Depletion in Human Decision Making. Frontiers in Psychology.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Burn-out: An occupational phenomenon.

- CIO.com. (2024). Burnout: A chronic epidemic in the IT industry.